When companies decide they need better user experience, the default move is often simple: hire a UX designer. But without clear outcomes, roles, or a team model, that hire rarely fixes the real problem. And that person ends up covering research, flows, UI, strategy, and constant “quick fixes” – creating bottlenecks, burnout, and inconsistent results.

Here’s the reality: UX isn’t one clearly bounded area. It’s a function that connects user needs, business goals, and product development. When that function lacks clear structure, boundaries and ownership, even strong UX professionals struggle to deliver impact.

In this guide, you’ll see which UX roles you actually need, how teams are commonly structured, how hiring typically evolves as you grow, when a one-person UX team can work, and which workflows help agile teams avoid burnout.

Without further ado, let’s get started.

Unpacking what a UX team actually does

UX work spans multiple specialized disciplines, even when it’s handled by a small team or a single person. Hence, if you’re trying to build a design team intentionally – first start with clarity about the work itself.

What UX teams are actually responsible for

What looks like "one UX job" spans several specialized disciplines, each contributing its own part to the bigger picture. Here's what that looks like in practice.

Product/UX Design

Focuses on interaction patterns and user flows – mapping how users move through your product, creating wireframes and prototypes, and ensuring the experience is intuitive. For example, a product/UX designer might map out the user sign-up flow, design the screens for each step, and test a clickable prototype to ensure the experience feels clear and intuitive before development begins.

UX Research

Prevents your team from designing in a vacuum. Researchers conduct user interviews, run usability tests, analyze behavior data, and translate findings into actionable insights. UX research shows exactly why users abandon your checkout flow or what features actually matter.

UI or visual design

Handles layout, visual hierarchy, and consistency. In many teams, product designers cover this work; in larger teams, dedicated visual designers help maintain quality and speed at scale.

Content design or UX writing

Shapes the language inside the product – crafts button labels, error messages, onboarding flows, and microcopy that guides users smoothly. UX writing often gets overlooked until interface copy starts confusing people and creating friction.

Information architecture

Ensures content and features are structured in a way users can understand what they need without navigation chaos. Sometimes, information architecture is a distinct role, but quite often it’s a shared skill across the team.

DesignOps

Becomes critical as teams scale – maintaining design systems, managing tooling, setting up workflows that let designers focus on design and move faster without sacrificing consistency.

UX Engineering

In some teams, this role sits at the intersection of design and development, turning wireframes and prototypes into production-ready UI components. This isn’t a core responsibility of most UX teams, and not every team has a UX engineer role, but it can be useful in component-heavy products.

In reality though, early-stage teams usually have one or two people covering multiple disciplines. As you scale, you split responsibilities based on workload and complexity.

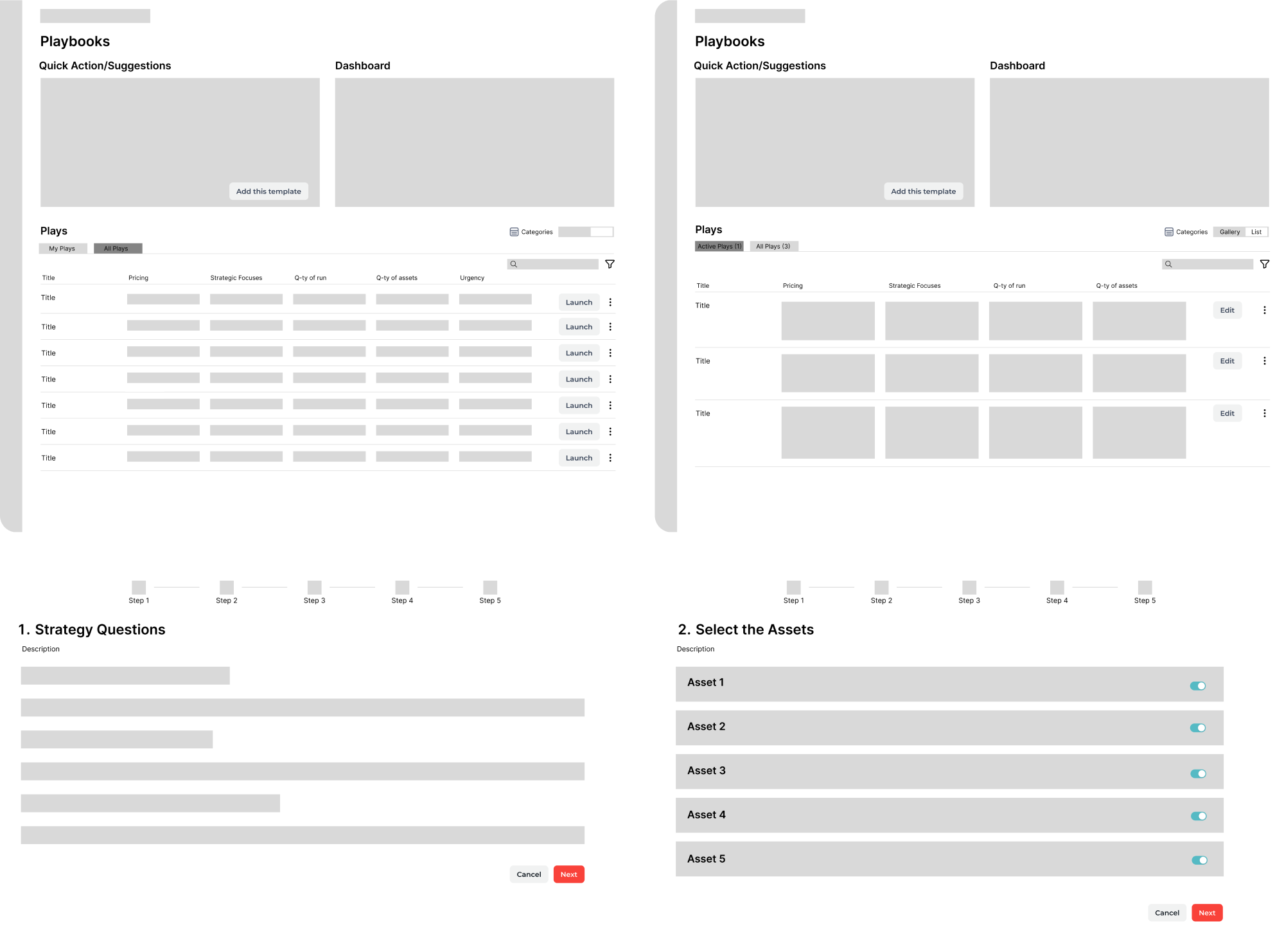

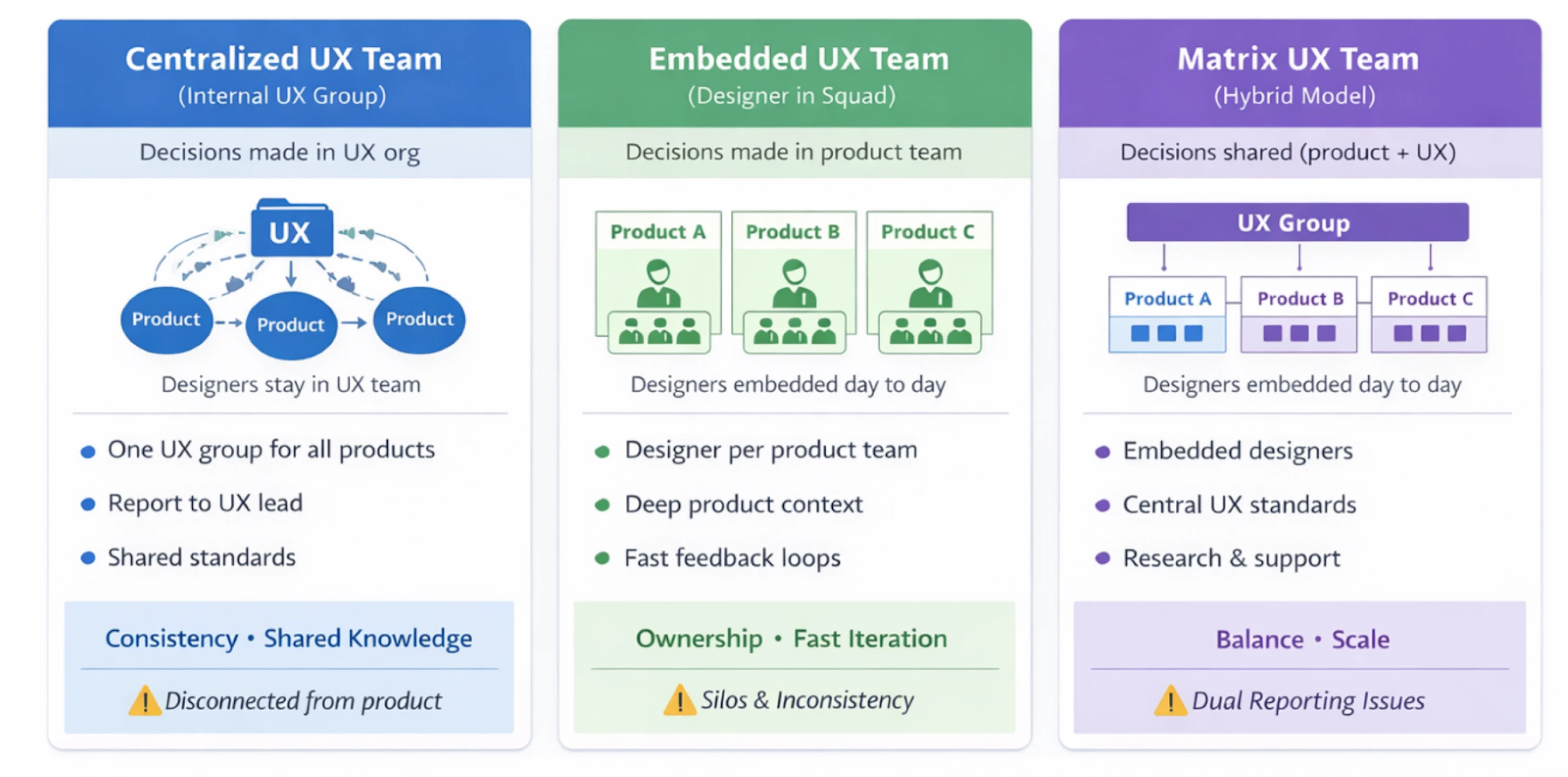

Choose your UX team model: centralized, embedded, or matrix

Once you understand what UX work includes, the next question is how to organize it. There’s no universal “best” UX team structure – your company size, product complexity, and development process all influence which structure works.

Most companies use one of the following three models:

1. Centralized UX team (“internal agency”)

In a centralized model, all UX professionals report into a single UX leader and support multiple product teams. When design support is requested, the UX manager assigns people based on priority.

Works best when:

- The company is early-stage or scaling unevenly

- UX work is project-based or done when needed

Benefits:

Knowledge sharing is easier, UX practices stay consistent and resource allocation is flexible.

Risks:

Designers become order-takers rather than strategic partners. They feel disconnected from product decisions, can miss critical context or may become overloaded without clear prioritization.

2. Embedded (decentralized) UX team

In an embedded model, designers are permanently assigned to cross-functional product development teams. They sit with engineers and PMs, attend sprint rituals, and report to a product lead.

Works best when:

- You have multiple product streams

- Teams ship continuously

Benefits:

Designers have deep product context, and can influence decisions early on. Collaboration is tighter, and feedback loops are faster.

Risks:

Design consistency can suffer, teams work in silos, and duplicate efforts. Junior designers lack mentorship, and capacity is harder to rebalance if workloads become uneven.

3. Matrix (hybrid) UX team

The matrix model combines both approaches. Designers work day-to-day within product teams but also belong to a centralized UX group for standards, coaching, and growth.

Works best when:

- Growing companies (5-15+ designers)

- Consistency and product depth both matter

Benefits:

Designers get deep product involvement along with peer community support. Research and design systems can be centralized to support multiple teams.

Risks:

Dual reporting can cause confusion unless roles, decision ownership, and priorities are clearly defined.

Making the choice

There’s no permanent “right” UX team model. The key is choosing a structure that matches how your teams work today – and revisiting it as your product and organization evolve.

UX team of one: can you survive?

A UX team of one is far more common than it sounds. Startups, early-stage products, and even growing companies often rely on a single UX professional to cover all design work. The real question isn’t whether this setup is ideal – it’s whether it can function without becoming a bottleneck or burning someone out.

When a one-person UX team is totally ok

Before you rush to hire a designer, it’s worth clarifying what problems you actually expect UX to solve. A solo UX setup can work when scope is narrow and expectations are realistic. This is often the case in early-stage products, limited feature sets, or teams with strong alignment between product, engineering, and leadership.

In practice, this is a setup we see often at Eleken UI/UX design agency. Many of our designers work as the only designer within a client team, fully embedded and owning UX end to end.

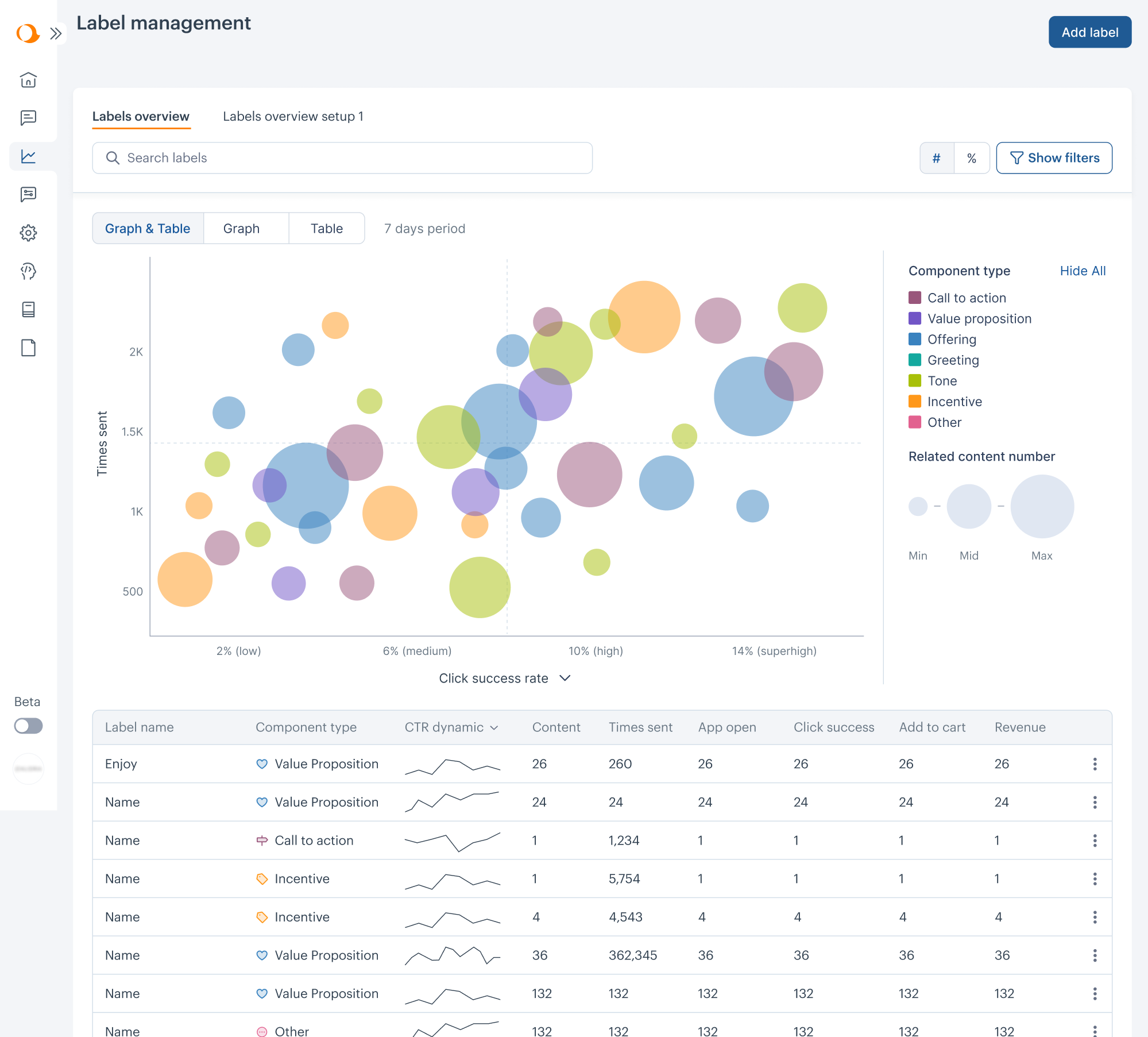

For example, Aampe, a data-heavy AI startup, needed urgent design help but couldn’t hire in-house fast enough. The founders – data scientists by background – lacked the skills to evaluate design candidates and hiring full-time was too slow. An Eleken designer joined as the sole designer on the team, integrated immediately, worked in fast-paced three-week sprints, and led platform redesign, accessibility improvements, and dashboard creation.

As the co-founder put it, it was “game-changing to get a full-time designer without the search or qualification process.” The collaboration worked so well that they kept the designer long term.

When expectations, scope, and ownership are clear, a one-person UX setup can move quickly, make informed trade-offs, and deliver meaningful impact without excessive overhead. But the key word here is can. Success still depends on setting realistic expectations from day one.

The common failure mode

Problems start when UX is treated as a person rather than a function. One designer is expected to conduct research, build flows, create UI, define strategy, deliver production-ready assets, AND handle an endless stream of "quick fixes" from stakeholders.

Context switching becomes unavoidable. Discovery work gets postponed. Short-term requests crowd out long-term thinking. Over time, the role becomes reactive instead of strategic.

And this isn’t a skill issue – it’s a structural one. Without boundaries, priorities, and support, even experienced designers struggle to maintain quality or momentum.

The UX community talks openly about this struggle. Solo designers describe feeling like an "execution machine" – overworked, understaffed, expected to have all the answers, and lacking anyone to sense-check decisions or think through trade-offs with.

That isolation is often what breaks one-person setups. When a solo designer has access to feedback, guidance, and shared expertise, the same setup becomes far more sustainable.

For example, at Eleken, designers may work as the only UX professional inside a client team, but they’re supported by a design lead and a broader team of 60+ designers they can consult when needed.

The difference isn’t how many designers you have – it’s whether UX is supported by a structure that enables strategic work instead of constant firefighting.

Make it survivable: minimum operating system for a solo UXer

If your product team has only one designer, here’s how to support them and keep things running smoothly:

- Set a single intake channel and run weekly triage

Make sure all design requests go through one place instead of Slack pings or informal asks. Review and prioritize requests together on a weekly basis.

- Limit work in progress and offer office hours

Avoid loading the designer with too many parallel tasks. Keep no more than two active projects running simultaneously, and introduce office hours for small or quick requests.

- Protect time for discovery

Ensure the designer has dedicated time for discovery work. Even a few hours per week can make a meaningful difference if it’s planned and protected.

- Aim for “good enough” research

You don’t need a full research program. Help the designer tap into insights from Sales and Customer Success, use product analytics, and support lightweight usability testing with a small number of users. Imperfect data beats no data.

- Agree on a Definition of Ready (DoR)

Before handing work to design, confirm that the problem, goals, and constraints are clearly defined. This saves time and reduces unnecessary rework.

These guardrails reduce reactive work and context switching, helping the designer focus on impact instead of constant triage.

When you need a solo designer (without hiring one)

Still, even hiring just one product designer can be challenging. Finding the right person takes time, onboarding takes effort, and the responsibility placed on a solo designer is immense – get this hire wrong, and every UX decision across your product suffers.

This is where partners like Eleken can step in and help. Our process is shaped by experience across 200+ product design projects, which makes it easier for an embedded designer to join quickly and work like an in-house hire – for as long as additional capacity is genuinely needed.

Besides, Eleken’s embedded designer is backed by a broader team of 60+ designers and supported by a design lead who reviews their work and provides guidance. So you get the feel of an in-house designer with the support infrastructure of a mature design team.

Team sizing & ratios: the reality check

Once you move beyond a UX team of one, sizing becomes the next challenge. There's no magic ratio, but understanding typical patterns helps you avoid the most common mistake: overloading designers with too many projects at once.

Where UX capacity hits limits – and what ratios work

Yep, the first sign a UX team is undersized isn’t visual quality – it’s overload. Here are common warning signs:

- Designers attend many meetings but struggle to move work forward

- Research and validation are repeatedly postponed

- Designers support too many stakeholders at once

With that, context switching increases, discovery gets deprioritized, and delivery slows.

In practice, the ranges below tend to be reasonable:

- Designers to PMs: ideal 1:1, survivable short-term at 1:2

- UX researchers: 1 researcher can typically support ~3 product teams

- Design systems / UI: can scale across teams, but only with clear ownership

Once teams exceed these ranges, sustaining quality and speed often gets challenging.

How to estimate headcount (simple method)

While ratios are useful reference points, they make the most sense when grounded in real workload. Here's a straightforward way to figure out what you need:

Step 1: List your squads and roadmap themes.

Three product squads actively shipping? That's three embedded designers minimum (1:1 with PMs). Five roadmap themes but two squads? You're under-resourced or need to prioritize.

Step 2: Identify "always-on" work.

Bugs, support requests, small improvements – this never stops. If it takes 30% of one designer's time, either accept it or add dedicated capacity (a "firefighter" rotation for bigger teams).

Step 3: Decide on coverage model.

Embedded designers in every squad = X designers for X squads. Centralized pool that rotates = fewer people, but slower response times and weaker product integration.

Output: Your "minimum viable team" number. The math isn't perfect, but it's honest. Anything below your estimated baseline equals survival mode – harming both quality and velocity.

How to grow a UX team stage by stage

UX hiring works best when it follows product reality, not org charts. The roles you add – and when you add them – should reflect product complexity, delivery pressure, and how much UX work actually exists. Below is a pragmatic way to think about hiring as your UX team grows.

Stage 1: UX team of one (0→1)

The first UX hire is the hardest. This person isn’t just joining a team – they’re setting the foundation for how UX works across the product.

Here's what to prioritize when hiring from zero to one:

1. Strategic thinking over visual craft

Your first designer needs to think problem-first, focusing on outcomes, not just screens.

What to look for:

- Can they explain why they made design decisions, not just what they designed?

- Do they talk about outcomes (adoption, errors reduced) instead of deliverables?

- Have they worked directly with PMs or founders before?

Red flag: portfolio focused only on visuals or Dribbble-style case studies without business context.

2. Comfort with ambiguity (this is non-negotiable)

As the only designer, they will juggle research, UX, UI, and delivery – switching context constantly and working without design leadership or validation.

What to look for:

- Past experience as a solo or first designer

- Clear examples of working with incomplete information

- Ability to set boundaries and say “no” constructively

Red flag: they wait for perfect briefs or get paralyzed without detailed requirements.

Speed and resourcefulness are what matter here. Your first designer sets the foundation – hire someone who works smart with what's available and doesn't wait for ideal conditions, and you'll set the stage for steady progress.

Stage 2: From one to three designers (1→3)

This stage is about scaling design work carefully. More designers mean more output, but also more need for alignment.

Option 1: Hire a senior generalist.

- Pros: speed and autonomy. A senior designer owns entire features and makes decisions independently.

- Cons: expensive, and you're still just two people.

Option 2: Hire a mid or junior designer.

- Pros: increases throughput for tactical work.

- Cons: adds coaching load to your founding designer.

How to split work among 3 designers:

- By product stream: Designer A owns onboarding. Designer B owns core workflows. Designer C owns settings. Each builds deep domain expertise. Risk: silos form without coordination.

- By specialty rotation: One designer leads research each quarter. Another focuses on UI. The third handles prototyping. Rotate to prevent burnout. Risk: unclear ownership.

Handling bugs and "small asks": Dedicate one designer as the "firefighter" each week (rotate weekly). That person handles urgent fixes while the other two get protected time for strategic work.

At this point, lightweight structure becomes important. Regular design reviews, shared standards, and a clear intake process help prevent fragmentation.

Stage 3: From three to around ten designers (3→10+)

Once the team reaches this size, specialization starts making sense. You have enough volume to justify dedicated roles.

Common additions at this point include:

- First UX researcher (often the biggest quality boost)

One researcher can support multiple product designers by planning studies, running usability testing, and synthesizing insights. Decisions shift from assumptions to evidence, and teams gain confidence in what they ship. - Content designer or UX writer (as complexity and UX debt grow)

This role addresses unclear labels, inconsistent terminology, and confusing messaging. Over time, it also helps establish information architecture that scales across features and teams. - DesignOps or design system owner (when inconsistency starts costing speed)

Instead of teams reinventing components and patterns, this role maintains the design system, tooling, and standards—helping everyone move faster without sacrificing quality.

At this stage, team structure often evolves in one of two ways:

- Embedded designers with shared research.

Each product team has a dedicated designer, while a researcher rotates across squads. - Embedded pods with a centralized design system team.

Designers are fully embedded in squads, supported by a small team (often two to three people) that owns the design system full-time.

The goal at this stage isn’t to add titles – it’s to reduce friction, improve consistency, and free designers to focus on higher-impact work.

Stage 4: Beyond ten designers

At this scale, the focus shifts more to creating transparent career paths for growth without adding unnecessary bureaucracy.

UX leadership roles – leads, principals, managers – should represent different ways of contributing, not status markers. Transparent decision-making, and shared expectations for each path help designers grow, take on responsibility, and be recognized for impact.

Governance should stay lightweight and transparent. Regular design syncs to share work in progress, and periodic design reviews for quality feedback help teams stay aligned without adding friction.

In case with distributed design teams, invest in async communication. Written briefs, recorded reviews, and clear documentation make collaboration scale – using meetings only when real-time discussion truly adds value.

Beyond the in-house model

Building an in-house team is the default path, but it's not the only one. In such cases, most teams seek to add capacity without restructuring their team or committing to long-term headcount. One approach is embedding an experienced product designer into the existing workflow to support ongoing work and relieve pressure.

At Eleken, for example, we work equally well with teams at the 0→1 stage (when hiring feels risky or slow) and with established teams that need additional capacity – like staffing for a major redesign or covering team gaps.

The key advantage is flexibility. If a product launch needs three designers, you scale up and bring them in. If the next quarter only needs one, you adjust and scale down accordingly. This lets you avoid the awkward cycle of hiring during peak demand, then searching for busywork (or worse, layoffs) when things get back to normal.

Basically, you get the capacity you need, when you need it, without the hiring stress and long-term obligations. Clean and simple.

How to run the team week to week

As teams grow, learning how to manage a design team day to day becomes just as important as hiring the right roles. Here's how to structure the work so design contributes to velocity instead of becoming a bottleneck.

How UX work really happens

A common way to think about UX flow is: discovery → concept → validation → delivery → release learning

In practice, teams often compress or overlap these steps. When timelines are tight, what matters is not rigidly following every step, but protecting intent:

- Discovery doesn’t disappear, it gets lighter

- Validation targets the highest-risk decisions

- Release learning informs what comes next

Not every team follows the same UX process, and that’s fine. Some stages may be skipped or combined — what matters is having a workflow that fits your team’s current needs.

Working with product and engineering

Let designers collaborate directly with product managers and engineers. They don’t need to attend every meeting, but they should be involved in key discussions so important details are aligned early and issues don’t surface later during development.

A simple division of responsibility keeps things moving:

- Product defines the problem, priorities, and success criteria

- UX shapes solutions and validates usability

- Engineering defines feasibility and technical constraints

When roles and decision ownership are clear, collaboration becomes faster and more effective.

Keep in mind: Designers don’t need to be in every meeting, but they do need to be involved early in planning and discovery. When UX is brought in late, product design risks turning into patchwork instead of a cohesive experience.

Measuring UX impact without heavy reporting

UX teams don’t need to track everything to show impact. A small set of meaningful metrics is usually enough.

Choose 3-5 UX metrics tied to business goals: Task completion rate, time to complete task, support ticket volume, conversion rate, satisfaction scores. Track them monthly or quarterly.

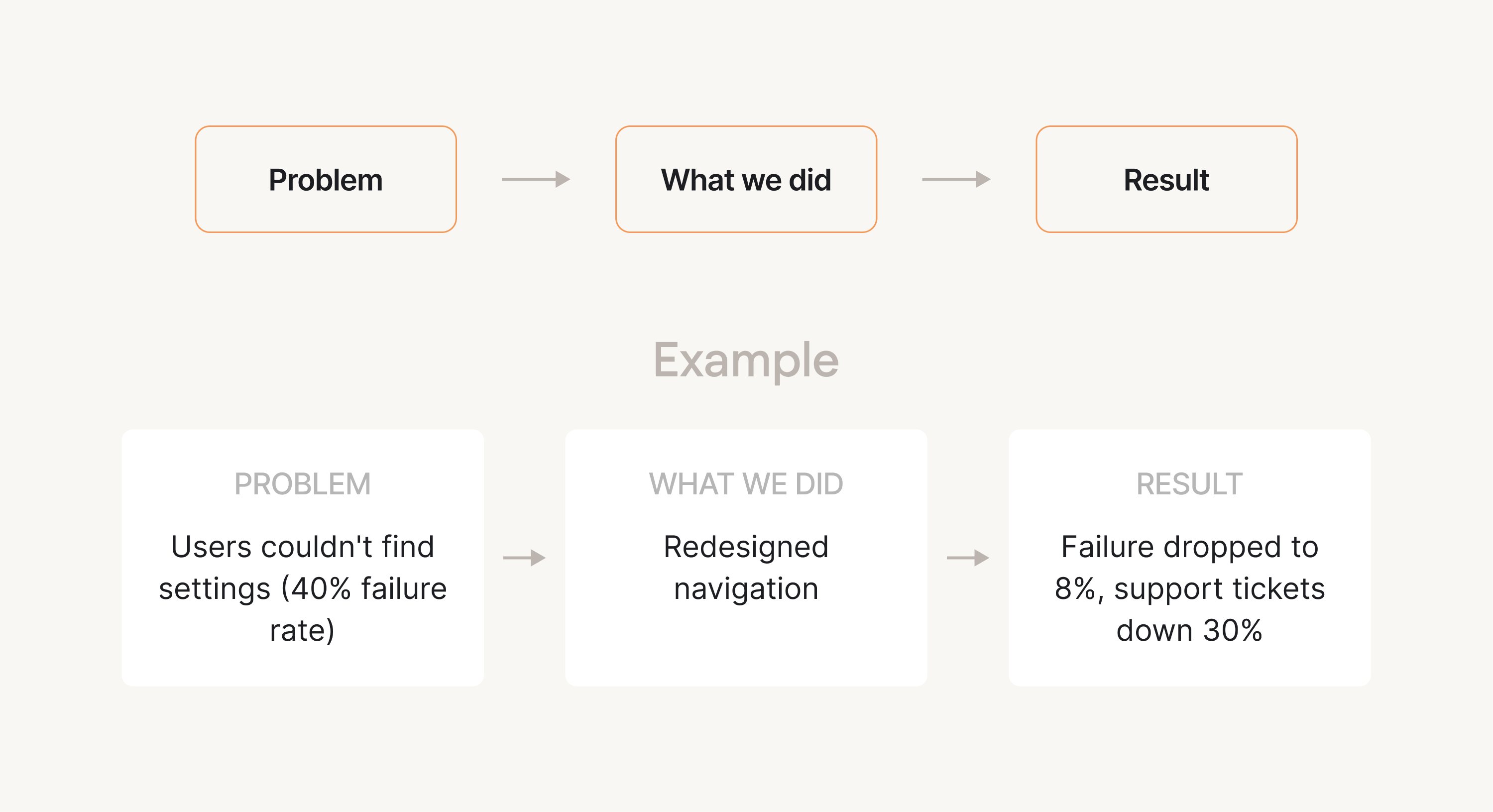

Alongside metrics, a lightweight impact log can go a long way.

This becomes especially useful when discussing priorities, defending UX time, or making a case for additional headcount—without turning UX into a reporting function.

Culture & retention: building a team that doesn’t burn out

Scaling a UX team isn’t just about structure and process. Long-term success depends on whether people can do good work sustainably. Burnout and turnover are usually the result of everyday decisions, not sudden failures.

Boundaries as a leadership skill (especially in remote/hybrid)

Burnout often starts with blurred boundaries. When designers are expected to be constantly available, focus drops and stress builds over time.

Leadership plays a key role in setting and reinforcing boundaries by:

- Removing expectations of after-hours responses

- Protecting focus time and reducing unnecessary meetings

- Setting realistic timelines that allow space for thinking

When clear limits are clear and consistently upheld, teams can focus better, work sustainably, and maintain quality over the long term.

Importance of psychological safety and trust

Strong UX teams rely on trust. Designers need to feel safe sharing unfinished ideas, questioning assumptions, and giving honest feedback.

Psychological safety grows when decisions are transparent, feedback is constructive, and mistakes are treated as learning rather than failure. When trust is present, collaboration improves and teams move faster.

On motivation and growth

Retention improves when designers understand how they can grow. Clear expectations, regular feedback, and visible progression matter more than titles.

When designers see a future and feel supported, they’re far more likely to stay engaged and retention grows over time.

Building UX for the long haul

All in all, building a design team isn’t about following a fixed formula or hiring every role at once. It’s about making clear, stage-appropriate choices that fit your product, your organization, and how work actually gets done.

Strong teams start by understanding what UX work includes, choosing structures that support collaboration, and growing reasonably as demand increases. As you scale, focus on sustainable workflows, clear ownership, and realistic expectations – so quality improves instead of degrading under pressure.

Yet, culture matters just as much as structure. Clear boundaries, transparent growth paths, and lightweight coordination help teams avoid burnout and improve retention over time.

And if you need to scale design capacity quickly – or adjust it as priorities shift – consider working with Eleken. Embedded designers can extend your team without long hiring cycles, helping you keep delivery moving without sacrificing quality and team focus.

.png)